How Trump-era Medicaid cuts could impact the privately insured

Published in Political News

Federal cuts to Medicaid passed under President Donald Trump’s signature legislation — dubbed as the “big, beautiful bill” — are raising concerns among Maryland health advocates and policymakers who warn the changes could affect not only low-income residents but also those with private insurance.

More than 1.5 million adults and nearly half of all children in Maryland are covered by Medicaid, according to the state Department of Health. While the bill’s provisions phase in over time, experts say the long-term impact could be significant.

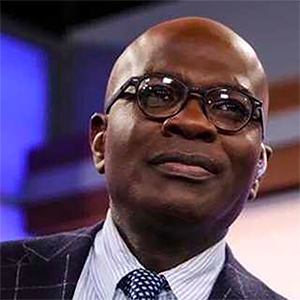

“In Maryland, when someone is uninsured and can’t get health care and go to the emergency room and is taken care of, we all pay higher premiums,” said Vinny DeMarco, the president of Maryland Health Care for All, a coalition of faith, business, labor and professional communities across the state that advocate for affordable health care access, said. “It would be bad for the uninsured and bad for all of us if Medicaid was drastically cut.”

What’s in the bill

Though Trump signed the bill Friday, most of its provisions — including Medicaid work requirements — will not take effect immediately. Medicaid recipients will not instantly lose access to their health insurance.

For example, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, work requirements would begin in January 2027. By the end of 2025, U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. must develop a plan for implementing the law.

The potential shift in Medicaid spending has particularly concerned state lawmakers.

During a briefing of the Maryland legislature’s Joint Federal Action Oversight Committee last week, David Romans, a fiscal analyst for the nonpartisan Department of Legislative Services, said that, under the bill before it was amended in the U.S. Senate, Maryland could be out “somewhere in the neighborhood of” $100 million between SNAP and Medicaid cuts for fiscal year 2026.

Those numbers increase dramatically — between $300 million and $450 million — in the years that follow.

Romans also said that up to 130,000 Medicaid recipients in the state might lose coverage due to work requirements and more frequent eligibility redeterminations.

Marylanders with questions about their health care coverage under Trump’s new policy can reach out to the Maryland Insurance Administration’s Health Coverage Assistance Team by emailing hcat.mia@maryland.gov or calling 410-468-2442.

Effects on health providers

For safety-net providers like Health Care for the Homeless, which serves about 11,000 people annually, Medicaid is a critical funding source. The group says roughly 60% of its patients are insured, and more than half of those rely on Medicaid.

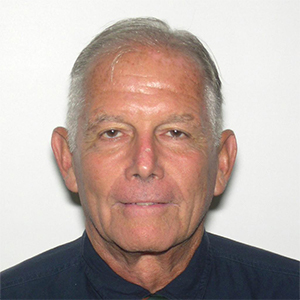

Kevin Lindamood, the organization’s president and CEO, said maintaining eligibility is already a challenge for many — especially those experiencing homelessness who might lack documentation or a stable address.

“If you’re experiencing homelessness, you often have lost track of all of those things. I mean, I don’t know if I could find my own birth certificate if you asked me to find it right now,” he said. “In a lot of cases, you have to have ID to get ID, so just proving your eligibility and maintaining it is complicated.”

Currently, Medicaid recipients in Maryland must recertify their eligibility annually. The new law shortens that to every six months, which could increase the chances of people losing coverage due to paperwork lapses. Health Care for the Homeless serves as the mailing address for many clients, but Lindamood said it’s common for individuals to miss critical forms or fail to follow up.

“Our mailroom is absolutely filled with recertification packets,” he said. “We try to get people their mail, but often they miss it. They don’t come back for it. They fall off the program.”

Debating work requirements

One of the more controversial aspects of the bill is its work requirement provision. Proponents argue it could reduce dependency and government waste. The Trump administration has framed the measure as a way to curb fraud and encourage employment.

According to the Brookings Institution, a nonpartisan research organization based in Washington, D.C., work requirements in public assistance programs often create administrative hurdles without significantly improving job participation.

The Kaiser Family Foundation, a California-based policy and research organization, found that 92% of Medicaid enrollees under age 65 who aren’t on disability are already working, attending school, serving as caregivers or are ill.

“You’re only talking about this extremely small subset,” said Lindamood, who also warned that verifying work status could increase administrative costs and reduce funds available for direct care.

For Del. Matt Morgan, a Republican representing St. Mary’s County,work requirements will stop abuse and bolster personal responsibility.

“It’s not [a] taxpayer responsibility to provide for able-bodied people what they should be able to provide for themselves,” Morgan said.

Broader impact on the insured

Maryland’s Total Cost of Care Model is designed to stabilize health care costs by setting uniform rates for hospital services. The model helps prevent cost-shifting from uninsured patients to insured ones by baking uncompensated care into hospital rates. Rates for care, which differ by hospital based on their ability to provide those services, are set by the Maryland Health Services Cost Review Commission.

But that model is set to expire at the end of this year and will be replaced by the All-Payer Health Equity Approaches (AHEAD) Model. It’s similar to the state’s current system, but with an emphasis on primary care.

DeMarco, whose organization supports Medicaid expansion, said cutting the program could reverse years of progress in lowering Maryland’s uncompensated care costs, which dropped from over $1 billion in 2008 to $842 million in 2022. A significant portion of that decline, he said, is attributed to Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act.

“Our studies that we’ve conducted show that, by decreasing the uninsured amount from 13% to 6% primarily through expanding Medicaid, we reduced uncompensated hospital care by over $460 million,” he said. “That’s over $460 million that would have gone right into our health insurance premiums.”

DeMarco cautioned that many Medicaid recipients do not earn enough to afford private insurance alternatives.

“I don’t think very many — if any, at all — people who use Medicaid will go on private insurance,” he said. “There may be some, but very few.”

------------

©2025 The Baltimore Sun. Visit at baltimoresun.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments