Review: Michelle Williams finds the modern spiritual essence of Anna Christie at St. Ann's Warehouse

Published in Entertainment News

Michelle Williams seems to have unlimited emotional access. Her inner intensity expresses itself in a frenzy of volcanic feeling that can never be tamped down once it reaches its boiling point.

There's a fragility to her best screen work, a sense that at any moment her character might crack into a million pieces. In such films as "Brokeback Mountain," "Blue Valentine," "Manchester by the Sea" and "My Week with Marilyn," she provides an X-ray into the women she's portraying, exposing the cracks beneath the exquisitely observed facade.

In the Broadway production of "Blackbird," Williams played a woman who confronts the older man who sexually abused her when she was 12 years old. Her character has tracked him down for a reckoning that is all the more anguished for being so dangerously ambiguous.

Anguish and ambiguity are perfectly compatible in the world that Williams inhabits. In the new revival of Eugene O'Neill's "Anna Christie" at St. Ann's Warehouse in Brooklyn, she gets to display not only her patented emotionalism but also a strategic restraint that keeps every option open.

The play, one of the few by O'Neill that swerves from tragedy to what might be called tragicomedy, allows Williams not only an opportunity to dive headlong into shame and resentment but also to withhold what she's really thinking and feeling. With an eye out for the next drink, she plays her cards as best she can in a game that's rigged heavily in favor of the men.

The play earned O'Neill his second Pulitzer Prize for drama, but he fumed at the way critics accused him of copping out with what seemed to them a happy ending. He didn't think his resolution assured anyone of anything. In a letter to critic George Jean Nathan, he described the conclusion as "merely the comma at the end of a gaudy introductory clause, with the body of the sentence still unwritten."

Later, O'Neill would renounce the play as a repository of "all the Broadway tricks" he had amassed in his "stage training." "Anna Christie" is marred by melodrama, heavy-handed symbolism (such as the fog that clouds the future of characters whose lives are dependent on the sea) and immigrant dialects (Swedish and Irish) that can seem clunky to a modern ear.

But there's a primal quality to the play's conflicts that endows the work with an eternal vitality in the theater. Anna, a former prostitute hard done by life, arrives in New York seeking shelter from the father with whom she has long been estranged. She's recovering from an illness and needs his help, even though she still hasn't forgiven him for abandoning her in her youth.

Chris Christopherson (Brian d'Arcy James), the long-absent paterfamilias, is a sorry drunk of a man who has traded the high seas for a New York coal barge, where he's the grizzled old captain. Full of regret for not having protected his daughter, who was raped by her cousin on the farm in Minnesota where she was raised, he hopes to make amends without having to assume too much responsibility for what happened to her.

Enter Matt Burke (Tom Sturridge) in a literal splash of an entrance. This Irish stoker with a wild temper washes up on the barge where Anna is now living with her father. After she nurses him back to health, Matt falls madly in love only to freak out when he learns about her sordid past. Chris doesn't want his daughter to be mixed up with a volatile man of the sea, but Anna is heartbroken that a chance at redemption is slipping away.

O'Neill resolves the triangular conflict with a combination of religious fervor, metaphoric brooding and scabrous humor. The play doesn't have the maturity of his masterworks, but the role of Anna continues to attract mighty talents.

Pauline Lord, who may be the finest American actor you've probably heard nothing about, was the original Anna in the 1921 Broadway premiere. Greta Garbo starred in the 1930 film, advertised with the tagline "Garbo Talks!" Two other Scandinavian greats, Ingrid Bergman and Liv Ullmann, couldn't resist essaying a part that passionately called out to them. In the 1993 revival, the last on Broadway, Natasha Richardson starred opposite the man who was to become her husband, Liam Neeson, in a production that was notable for the powerhouse acting and for the romantic sparks engulfing the leads onstage and off.

The role of Anna is a technically demanding one. Williams has to maintain not only the period of the play but also its cumbersome patois. Although she's significantly older than her character, she seems better preserved, as though there's a stylist working the docks.

As Chris, Brian d'Arcy James, who would be one of the first picks on my all-star theater team, seems as if he's really pounding those whiskeys at the New York waterfront saloon in which the play begins. It's not easy to portray a drunk truthfully. James, who starred in the alcoholism-themed musical adaptation of "Days of Wine and Roses," shrewdly concentrates on the physical swoosh and repetitive patter of his character. Chris is entertaining his bedraggled companion, Marthy Owen (Mare Winningham, who holds her own opposite James' skid row master class).

One wouldn't say of Williams' Anna, as the drama critic Stark Young (imagining the commentary of a late French titan of acting) said of Lord's Anna, "You had there, in your tragic eyes and your frail body and your haunted voice, all the store of your wrongs and your suffering…" The external demands of the role aren't an exact fit for Williams, but she finds the spiritual essence of her character.

Her Anna shares Chris' fixation on the next drink, an inheritance she betrays with a darting eye. But it's the deeper complexities of Anna's situation that Williams illuminates so powerfully.

Paradox defines a character who feels tainted yet knows herself to be pure. Dependent on the kindness of near strangers yet fiercely autonomous, Anna has survived too much to give up now. She can't absolve her father of his failures, but she can offer him — and herself — another chance.

Sturridge's performance is almost expressionistic in its fiery passion and menacing violence. He plays Matt as if the character were a manifestation of "the old devil sea," one of the refrains of a play that finds maritime metaphors for all that is uncontrollable in human life.

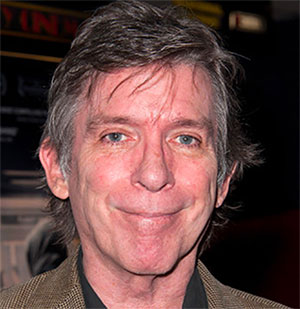

The production, directed by Thomas Kail, who won a Tony for his electrifying work on the musical "Hamilton," incorporates the movement of Steven Hoggett, an expert at choreographing dramatic texts. Kail, who's married to Williams and directed her to great success in the miniseries "Fosse/Verdon," which he co-created, takes a stylized approach to the staging without sacrificing the weighty interior realism of his leads.

It's not easy managing the ponderousness of O'Neill's writing. But Kail's fleet maneuvers keep the production from bogging down without lessening the emotional combustion that is the source of the playwright's lasting genius.

When Matt learns that the woman he wants to marry has sold herself to other men, he erupts in paroxysms of murderous rage. Williams' Anna absorbs his fury as though it were the penance she herself would mete out for her sins. Yet she knows the history that reduced her to such a debased state. Like Oedipus, she's both subjectively innocent and objectively guilty.

Matt, however, can't shake off his love. He insists that Anna utter the holy vows that can ease his mind. She complies with the fervor of a novitiate. At the same time, she can't help laughing at the irony of a deity who arranges things in such a ruefully comic way. Chris and Matt, who have been at each other's throats, will be shipping out together, forced to reconcile as newfound family members.

Williams' shift from prostrate grief to helpless amusement hints at hidden dimensions of a character who will always be a couple of steps ahead of the men trying to control her. But O'Neill was indeed truthful about the ending. Winningham's Marthy doesn't have to appear to hover as a specter of Anna's unglamorous future.

One battle may be won, but life is a war that permits no permanent victory. Williams complicates O'Neill's vision with her modern take on a woman forced to rewrite her own story.

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments