Chris Jones: The Stratford Festival of theater rediscovers a beating Canadian heart

Published in Entertainment News

STRATFORD, Ontario — Settling in my seat for “Annie” at the Stratford Festival of Canada, I awaited with perennial pleasure the overture’s trumpet solo for “Tomorrow,” followed by the chirpy sounds of “It’s the Hard-Knock Life,” a masterful little combo that first argues for optimism at all times before empathizing with our daily grinds.

But it didn’t happen. Instead, the 1,800 people inside the sold-out Festival Theatre here rose to their feet and sang the music of Calixa Lavallée, not Charles Strouse: “O Canada, Our Home and Native Land.”

The moment was striking because in some 30 years of attending Canada’s most prominent theater festival every summer, I’d never heard the Canadian national anthem sung at a regular performance of a show. The Stratford Festival, founded by a British man, dedicated to a British playwright and popular with Chicagoans and other Americans for decades, had always existed within a kind of multinational, English-language detente. This year, surely as a reaction to President Donald Trump’s rhetorical campaign to render Canada the 51st state, it just felt a whole lot more Canadian. At the Avon Theatre, during the intermission for that most Canadian of stories, “Anne of Green Gables,” my eyes fell on the ice cream case, as they are wont to do. The outside of the fridge said Breyers. But inside was a local Ontario brand, McFadden’s. Delicious.

All that said, Americans, the festival says, have been returning to Stratford this year: U.S. visitation is up by 4% year-over-year. There is also something of a local campaign in town to make them feel especially welcome. At Revel, a local coffee house and distinguished pastry purveyor, a sign on the counter asks American visitors to identify themselves. If they do, they are treated to a free coffee beverage, courtesy not of the cafe but of a local benefactor who prefers to just go by Stuart and who gets billed daily, and who wants Americans to feel welcome to the point of funding their cappuccinos. He’s the local version of Daddy Warbucks, whose crew likes to sing about how Annie “put sweet dreams upon our menu.” As indeed she does.

The year’s Canadian vibe, a very lively and ebulliently choreographed “Annie” aside, extends to most of the shows I saw here. The big hit this year is “Anne of Green Gables,” a beloved Canadian coming-of-age story by Lucy Maud Montgomery about another outspoken redheaded orphan, this one a denizen not of NYC but of Canada’s Prince Edward Island. As played by Caroline Toal, Anne “with an e” captures her audience almost the moment she walks out on stage.

A preexisting relationship and familiarity surely helped, although that can be a double-edged sword. I watched young Canadian girls and women all around me sizing up the ebullient but vulnerable Toal in a matter of seconds and deciding she will do very, very well. Indeed. Improbably, the spunky Toal is the star of the Stratford summer.

The new adaptation, written and directed by Kat Sandler, first sets the story within an outer frame, a book club taking on Montgomery’s novel, which is a conventional meta approach. It then makes the far bolder choice of abandoning the period setting halfway through and asking the question, “What would Anne be like today?”

The idea works strikingly well, partly because we’ve already experienced the heroine in her actual period, so it doesn’t feel as much like an imposition as other modernizations but instead feels helpfully ruminative, a stand-in for what every contemporary fan of the book typically wonders as they read.

“Anne of Green Gables” engages in a reconstruction of a broken family (not unlike “Annie,” which builds its own) and the key, whatever the period, is the relationship between Anne and her two surrogate parents, wound-tight Marilla (Sarah Dodd) and deadened Matthew (Tim Campbell). Although possessive of a very Canadian stoicism, the two siblings blossom once Anne comes into their lives and all three of these actors understand what they are about and their journeys are consistently honest and moving. I’d argue Sandler’s conceit, which is just as fun when Anne is dealing with her friends and love interests, overstays its welcome by a few minutes in the contemporary section. But with some judicious cutting, “Anne of Green Gables,” which has much akin with “John Proctor is the Villain,” and the same target demographic, strikes me as a very viable Broadway show.

Other evidence here suggests that Canadian theater, and Canadians in general, are doing better than their neighbors to the south at focusing on the core values that hold the nation together. Take, for example, “Forgiveness,” a new play by Hiro Kanagawa that is based on a memoir by Mark Sakamoto exploring how Canadians of Japanese origin with treated during World War II. As was the case in the U.S., anyone who looked Japanese was rounded up in Canada and treated poorly in work camps and the like, decimating families and traumatizing those who felt as Canadian as anyone else. “Oh Canada,” one Japanese Canadian character cries out. “I don’t know if I can ever forgive you,” which is a central question of the show.

There are, of course, many angry plays looking back on radicalized ill-treatment from the past. Most of such U.S. pieces fundamentally are accusatory. But the aptly named “Forgiveness” also explores how conscripted Canadian servicemen were treated by the Japanese forces, who subjected them to horrific camps of their own, thus in part explaining (in this play) the challenges Canadian veterans in supporting the subsequent interracial marriage of their own children. The piece, which is directed by Stafford Arima, is too subtle and sophisticated to claim equivalence, or to try and argue which was worse than the other. But the reality of most theater, of course is that the audience skews older, whatever efforts are made to the contrary, and the retirees who flock to genteel Stratford each summer are only one generation removed from those remembering World War II. “Forgiveness” functions not as a reckoning but as a dramatic truth and reconciliation committee that takes its viewers by the hand and helps them move forward to a multi-cultural and unified nation together. The piece is a tad lugubrious and struggles some with the common issues of dramatized memoirs that range across space and time. But Arima and his excellent cast keep us focused on arriving at the most moving of conclusions.

I took a while getting out of my seat after director Antony Cimolino’s production of “The Winter’s Tale,” which I’ve long felt to be the most moving of Shakespeare’s last plays, given that it proffers the ability to bring a loved one back from the dead, and someone who died due to the main character’s folly of myopia and narcissism. If you know the play, you’ll recall that the jealous King Leontes not only effectively kills his faithful wife, Hermione, but tries to get rid of his daughter, Perdita, who is saved only by an underling whisking her away in the nick of time. Thanks to merciful powers and his own much delayed self-knowledge, Leontes gets another chance with both of those loved ones. That’s always moving, especially when you have a deep well of an actor like Graham Abbey playing Leontes. But Shakespeare leaves Leontes and Hermione’s son, Mamillius, dead. He died from distress at his mother’s arrest and he usually just lingers at the end, unseen and unspoken.

Not here. In this production, he arrives accompanied by an angel. Leontes thinks he has got him back, too. But no. Not all of our mistakes can be corrected, Cimolino first seems to be saying. But the exquisite moment then suggests that Mamillius can still forgive from immortality, and thus Leontes still can be forgiven. It’s affirmative and deeply sad. I won’t quickly forget the end of this summer telling of “The Winter’s Tale.”

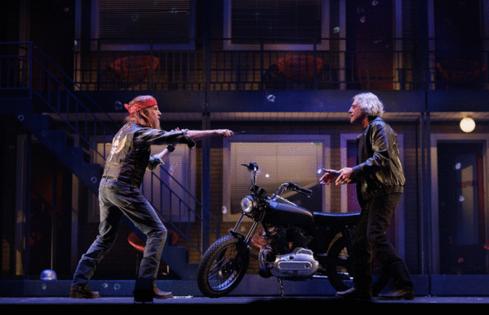

On this trip, that leaves me with director Robert Lepage’s “Macbeth,” a wacky production that imagines the Scottish play as a feud between coke-snorting bikers. Settings include a roadside motel, from a balcony wherein Lucy Peacock’s all-in Lady M falls most theatrically, a gas station and a parking lot with outdoor grills, the flame-throwing lair of the twisted sisters. When Macbeth meets his preordained fate, Birnam Wood arrives in the form of bikers riding what look like real bikes, all carrying little verdant trees on their handlebars.

There’s another rub too. Tom McCamus, who plays Macbeth, is a 70-year-old actor and a great veteran star of this festival, as is Peacock, a fine foil. That’s a cool idea. Most of Shakespeare’s characters shift in age according to which scene you are in. No reason not to push that envelope a bit with an actor of this skill and lucidity,

Alas the concept, which uses the cinematically fused iconography familiar to we longtime fans of LaPage, doesn’t really work because it doesn’t establish enough gravitas among the biker gangs to really make you believe they are dealing with matters of honor and destiny; it is as if the characters are putting on the drama, which can work fine with many of the Bard’s works, but not this one. Macbeth is meta all by itself. It does not need any frame for it work its horrors.

Still, any festival of Canadian identity — even if I think that mostly is unconscious — has to deal with the Quebecois, the yang to the yin of rural Ontario, which isn’t far removed from Minnesota nice. That only gets you so far with the Scottish play. Lepage always offers a little Francophone disruption wheresoever he roams, disruptingly, and “Macbeth” never really works, anyway. Except on us poor suckers who fall prey to its curses.

———

The 2025 season of Stratford Festival continues in Ontario continue through late fall; tickets and more information at https://www.stratfordfestival.ca/

———

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments