Commentary: Bruce Springsteen's 'Tracks II' is an epic act of rock star lore

Published in Entertainment News

LOS ANGELES — Fifty years after he became a sweat-soaked rock star with 1975’s “Born to Run,” Bruce Springsteen has opened up his vault of unreleased material for a new box set that spans nearly the length of the half-century he’s spent chasing a runaway American dream.

“Tracks II: The Lost Albums” collects 83 songs, the vast majority of them unheard by even devoted fans of the Boss. It’s a sequel of sorts to 1998’s “Tracks,” which offered up demos and outtakes to fill out the story of one of music’s most prolific and meticulous songwriters. But unlike the earlier set, “Tracks II” organizes its songs into seven distinct LPs, each with a different sound and theme; Springsteen says he came this close to releasing some of them at the time they were made but ultimately decided not to for various reasons related to his life and career.

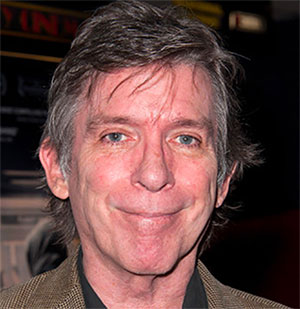

As a project of pop archiving, “Tracks II’s” breadth and depth put it on par with Peter Jackson’s Beatles docuseries “Get Back” and with Taylor Swift’s series of “Taylor’s Version” rerecordings. And it arrives at a time when Springsteen, 75, is already in the headlines thanks to his war of words with President Donald Trump over the latter’s aggressive deportation policies and to the recently unveiled trailer for this fall’s “Deliver Me From Nowhere,” in which Jeremy Allen White plays Springsteen. Times pop music critic Mikael Wood and staff writer August Brown gathered to discuss the box set and what to make of its bounty.

Mikael Wood: Let’s start with how Springsteen and his team are rolling out this behemoth. As I’ve interpreted the essays and videos and interviews that have set up “Tracks II,” they see the box set as an opportunity to reshape our understanding of the Boss in two ways.

The first is that he was ambivalent about rock stardom: “L.A. Garage Sessions ’83” is the earliest of the albums here, and it seems meant to disrupt the idea that Springsteen transitioned smoothly from the lo-fi “Nebraska” in 1982 to the arena-geared anthems of “Born in the U.S.A.” in 1984; this lost LP, which the singer cut mostly on his own in a little apartment above a house he’d bought in the Hollywood Hills, suggests that he was tempted to stay in that more writerly zone instead of lunging for the MTV of it all. To my mind, it’s making the argument that perhaps he didn’t go quite as eagerly as we thought — that even back then he was weighing the benefits and the costs of becoming a sex symbol in a pair of bum-hugging jeans.

The other thing I think “Tracks II” is trying to do is correct the record regarding Springsteen in the ’90s. He released three albums in the decade of grunge, none of which did particularly well (at least by Boss standards). Yet here are three more LPs that tell us he was busy experimenting at that time rather than merely waiting for Pearl Jam’s moment to pass: “Streets of Philadelphia Sessions,” which grew out of the moment that yielded his Oscar-winning theme from Jonathan Demme’s “Philadelphia,” has him dabbling in synths and drum loops; “Somewhere North of Nashville” is a frisky country record he made at the same time as the more contemplative “Ghost of Tom Joad”; “Inyo” takes inspiration from the Mexican music he says he heard while riding around Southern California on his motorcycle.

These acts of lore maintenance closely follow Springsteen’s memoir and his one-man Broadway show and a number of recent documentaries, and of course “Tracks II” is coming out right before the splashy biopic that promises to set off a Boss-aissance not unlike the one “A Complete Unknown” did last year for Bob Dylan. But what do you think, August, of this perceived need to adjust Springsteen’s framing? Does he strike you in 2025 as an artist that anyone might possibly have gotten wrong?

August Brown: I think you’re onto something, Mikael: This box is a reclamation of Springsteen as a challenging, skeptical songwriter even during the periods when his pop-culture status elevated him in ways that now seem inevitable — mythic, even.

There’s never been a more fruitful age for fans who want to dig under the hood of Springsteen’s process. The hugely successful Broadway show and his critically acclaimed book laid the groundwork for “Deliver Me From Nowhere,” which looks to capture him at the bleak, brilliant, transitional moment of “Nebraska.” That’s a time Springsteen has described as “depression … spewing like an oil spill all over the beautiful turquoise-green gulf of my carefully planned and controlled existence.” He compared depression to a “black sludge … threatening to smother every last living part of me.”

Can you imagine being a film exec who’s gotten the rights to a Bruce biopic only to be told you’re getting the story of his most impeccably miserable solo record?

But it comes alongside ”Tracks II,” which adds a ton of new texture and spiky context to the era when Bruce exploded from blue-collar ambassador into a global superstar. I agree that “L.A. Garage Sessions ’83” shows his mixed emotions about becoming the most famous tuchus in the country if that came at the expense of his literary aspirations. It’s wild to discover that as he was channeling the bombast of “Born In the U.S.A.,” he was also spinning out “The Klansman,” a brooding character study of American evil that promises, “When the war between the races leaves us in a fiery dream/ It’ll be a Klansman who will wipe this country clean/ This, son, is my dream.”

Wood: Talk about dancing in the dark.

Beyond the four albums we’ve mentioned, “Tracks II” also contains “Faithless,” which Springsteen describes as the soundtrack to an abandoned “spiritual Western” he was involved with in the mid-2000s; the snazzily orchestrated “Twilight Hours”; and “Perfect World,” which departs from the box set’s concept by simply rounding up 10 fist-pumping rock songs that never found a proper home as he recorded them over the last few decades. (In the essay that accompanies “Perfect World,” he says “If I Could Only Be Your Lover” almost made it on 2012’s “Wrecking Ball” — “but it wasn’t political enough.”)

Taken together, the variety of the work here makes you wonder: Is anyone more flexible among Springsteen’s boomer-royalty peers? I’d say Paul McCartney and Stevie Wonder are both capable of doing as many different things, though I’m not sure either has been driven to actually do them for ages. Taken one by one, the albums show how committed Springsteen was to each style he was taking up.

Brown: I especially like the horny-apocalyptic mode of “Waiting on the End of the World,” from “Streets of Philadelphia Sessions.” But I’ve been turning back most often to “Inyo,” which finds him squarely in the Townes Van Zandt mode of regally weary minimalism as he conjures scenes of the the California desert and border-town Mexico — a genre setting that feels especially resonant from our vantage point of an L.A. under siege.

Speaking of which: To me, one of the most interesting things about this set of narrative-upending albums is that it arrives at a Trump-dominated moment when Springsteen’s status as the bard of working-class white America is probably as inaccurate as it’s ever been.

I remember seeing Bruce back on 2004’s Vote for Change tour with openers Bright Eyes and R.E.M., imploring my fellow young Floridians to come out for John Kerry. (We all know how that turned out.) And it’s heartening to see him still on the road, laying into what he sees as the creep of totalitarianism every night in his eighth decade of life.

But who are we kidding? Any MAGA types who once would have listened to the Boss’ thoughts on organized labor and resisting fascism are probably gone forever — even if it does needle the actual ’80s Tri-State Area Guy currently occupying the White House. At best, those blue-collar dudes are in line today for Zach Bryan; more likely, they’re listening to Morgan Wallen.

Wood: I can’t imagine that the reported half-billion dollars Springsteen made in 2021 by selling his catalog did much to dissuade those inclined to view him as a coastal elite long since grown out of touch with the common man. (Bruce and Don: just two rich guys fighting for the soul of Lunchpail Larry.)

Your point about “Inyo” makes me think about how much of the “Tracks II” music grew out of Springsteen’s time in California, a place he seemed to view in the ’80s and ’90s as both a refuge from fame and a source of creative renewal. The essay accompanying “Streets of Philadelphia Sessions,” for instance, tells us that he cut the demos for that lost album at his place in Bel-Air, where he’d moved after his Hollywood Hills home was damaged in the Northridge earthquake; evidently, Springsteen started using drum loops because he’d gotten deep into West Coast hip-hop.

Given that this was early 1994, I wonder if he was also hearing Beck’s “Loser” on KROQ — something a song like the casually funky “Blind Spot” certainly suggests was the case. I like the idea that an artist so steeped in the history and mythology of New Jersey found his wheels turning in new directions here.

Brown: Whatever’s happened to his ability to rally the middle of the country, “Tracks II” shows that the one person Springsteen could always push was himself — wherever the muse took him, even at the height of his celebrity. I can see why he shelved these restless yet fully realized little albums, as they would have complicated his lore at a time when rock music was shifting underneath him, just before his 2000s renaissance with “The Rising.”

But they deepen and affirm what, I think, “Deliver Me From Nowhere” is trying to do for his ’70s era: demonstrate that Bruce’s ubiquity in the ’80s — and the new churn of rock in the ‘90s — left him uneasy and turning back to the sturdy craftsmanship and scene-setting experiments he loved. These records don’t reveal anything jaw-dropping about his ambitions, but they show that given the choice of being an artist or a hero, he never shortchanged the former even when the culture was begging for the latter.

I mentioned that “Inyo” is probably my favorite of the lost albums. How about you?

Wood: It’s probably the biggest outlier in the bunch, but I’m fascinated by “Twilight Hours,” which collects songs Springsteen cut during the sessions that yielded 2019’s “ Western Stars.” That record had a gleaming Glen Campbell vibe, but this one is moodier and more downcast; it leans toward the Sinatra of “In the Wee Small Hours,” with Bruce singing about loneliness and regret amid arrangements lush with horns and strings. (For a comparison, you might think of Elvis Costello and Burt Bacharach’s “Painted from Memory,” from 1998.)

Springsteen’s vocals here are intimate yet highly theatrical — a mode of “doomed romanticism,” as he put it in an interview with the Times of London. It’s a nostalgic record, for sure, but there’s something mysterious about it too, as though he’s not quite sure what precisely he’s longing for, or why. Like “Tracks II” as a whole, “Twilight Hours” is about the road untaken, and it sounds both haunted and enriched by possibility.

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments