Southeastern Pa.'s massive transit cuts are here, and it's 'bad on so many levels'

Published in News & Features

PHILADELPHIA — SEPTA, the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, warned us for two years.

Some people stopped listening because impoverishment has been the perpetual soundtrack of the transit system, and salvation always seemed to arrive at the last minute.

Not this time. Massive cuts in SEPTA service began early morning Sunday.

For the people who ride transit, it’s going to mean a million individual daily disasters.

For the Philadelphia region, the question is whether SEPTA’s retrenchment triggers an economic decline. America is littered with cities like Baltimore or Detroit whose growth and vitality suffered as their transit systems withered.

Disruption will be immediate.

On the first day of school Monday, more than 50,000 Philadelphia students will take unfamiliar bus routes to class, with more transfers. Traffic could clog as a share of 700,000 daily transit riders decide to drive. Late-shift workers will struggle to get home with more infrequent buses and trains at night.

“It’s going to be bad on so many levels for so many people, you can’t even quantify it. Day by day and week by week, it will get worse,” said Connor Descheemaker, coalition manager of Transit for All PA.

Worsening transit

SEPTA is cutting 20% of its service; 32 bus lines will be eliminated, including series 400 routes that serve schools, and 16 other routes will be shortened. Buses, trolleys, and subways will reduce the number of trips offered, lengthening waits for riders.

On Sept. 2, Regional Rail service will be reduced. That could mean up to two hours between trains in the midday hours during the week and on weekends.

And on Sept. 1, fares will increase 21.5% across the board. The base one-way SEPTA fare will be $2.90, equal to the New York Metropolitan Transit Authority’s price.

SEPTA has a $213 million hole in its operating budget and projects a continuing yearly shortfall of at least that amount until Pennsylvania enacts a stable, long-range source of new state funding for mass transit.

That has not happened as the divided legislature — a Democratic House and a Republican-majority Senate — has failed to agree on a transit-funding plan, or even a full-year state budget. It is almost two months late.

Things would get worse for Philadelphia in January if the dynamic does not change, with five Regional Rail lines eliminated, more bus routes axed, and all rail service stopping for a 9 p.m. curfew. (SEPTA won’t have enough money to provide turndown service for the sleepy trains.)

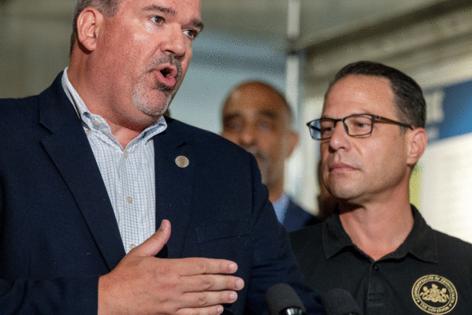

An intense partisan fight

There was a glimmer of movement.

Senate Republicans earlier this month passed a plan they said would provide a two-year bridge for SEPTA by shifting money from accounts in the Public Transportation Trust Fund that are reserved for mass transit capital projects, including upkeep, so SEPTA and other systems could pay operating expenses.

Along with e-gaming tax revenue, the proposal would have generated about $1.2 billion, roughly half to keep SEPTA and other transit systems operating, and the rest to fix rural roads and bridges.

House Democrats voted the next day not to consider the GOP Senate’s proposal.

SEPTA said it didn’t want to use money for needed infrastructure projects on day-to-day things, with no sign the capital funds would be replenished.

Democrats and public transportation advocates objected to using the state’s main transit funding mechanism on road projects, though most said they support getting more money for roads.

Republicans say it provided a basis for further negotiations and would have helped SEPTA while lawmakers worked out something more long-lasting.

Now an intense partisan fight has broken out, with Democrats betting they can flip the Senate in 2026 by defeating two Republicans in the southeast on the transit issue.

Not just SEPTA

Other mass transit agencies around the nation, including in Boston, Washington, and the Bay Area, are facing looming funding gaps. Some of it is because they are always scuffling for money from state and local governments, as well as fighting the effects of inflation and COVID-reduced ridership. Those are worsened by the end of federal operating aid given to mass transit during the pandemic.

Chicago stands out, with a deficit in the hundreds of millions of dollars. If the Illinois legislature does not act, half the branches of the Chicago Transit Authority’s famous L would stop. After 74 bus routes are cut, Chicago would have fewer than Kansas City.

The deficit for Chicago’s three transit services — CTA; a suburban bus system; and Metra commuter rail — stands at more than $500 million.

Illinois lawmakers could not agree on new funding sources before their session expired May 31.

The Illinois Senate passed just before adjournment a $1.50 statewide tax on food deliveries, as well as a real estate transfer tax in Chicago’s suburbs. It was too late.

“The House didn’t even know what was in there,” said W. Robert Schultz III, a campaign organizer for the Active Transportation Alliance in Chicago.

“Following the sausage analogy, people were throwing in sage and salting and taking out peppers and throwing in paprika up until the last minute,” Schultz said.

Cuts could start in January.

A way forward?

For cities like Chicago and Philadelphia, mass transit is trying to limp along with a 20th-century funding model and growing 21st-century mobility demands, experts say. People want to use transit in more flexible ways than traditional commuting to downtown. It takes big investments to adapt.

Philadelphia has been growing in recent decades after years of stagnation because it has key assets: transit connectivity, urban density, and an accessible workforce, according to a recent essay by Jeff Hornstein, executive director of the Economy League of Greater Philadelphia.

“These advantages are not permanent. They require continuous investment and maintenance,” he said.

It has proved hard in Pennsylvania and elsewhere to sustain public goods like transit. The political system rewards short-term fixes and abhors taxes.

Hornstein said the five counties in SEPTA’s service area should be empowered to levy local taxes dedicated to funding transit.

Last year officials from all five southeastern counties sent a letter to lawmakers, urging approval of legislation to broaden the counties’ options for gathering revenue through sales, wage, or transfer taxes.

Under state law, Pennsylvania’s collar counties are authorized to tax only property. Three of the four suburban counties increased property tax rates last year as expenses outpaced revenue.

Hornstein sees that kind of local option as a way to work around political hurdles.

He used the example of a half-penny increase in the sales tax, and says local revenue ideally could seed a regional transportation trust fund.

“We want you to give us the right to tax ourselves,” Hornstein said in an interview. “It’s no skin off anybody’s nose. This is our money, money that consumers would spend in Philadelphia.”

The MTA in New York, for instance, in 2009 got the state legislature to authorize a payroll mobility tax on regional employers. It generated $1.8 billion of the agency’s operations budget for buses, subways, and extensive commuter rail lines in 2024.

Facing the possibility of steep federal budget cuts, suburban county leaders said they anticipate little wiggle room in next year’s budget to devote more to SEPTA. Even if they had taxing options, they do not view a local tax as a replacement for sufficient state funding.

Meanwhile, the crisis is here. SEPTA cuts are happening.

(Staff writer Katie Bernard contributed to this article.)

______

©2025 The Philadelphia Inquirer. Visit inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments