Michael Hiltzik: Say farewell to the AI bubble, and get ready for the crash

Published in Business News

Most people not deeply involved in the artificial intelligence frenzy may not have noticed, but perceptions of AI's relentless march toward becoming more intelligent than humans, even becoming a threat to humanity, came to a screeching halt Aug. 7.

That was the day when the most widely followed AI company, OpenAI, released GPT-5, an advanced product that the firm had long promised would put competitors to shame and launch a new revolution in this purportedly revolutionary technology.

As it happened, GPT-5 was a bust. It turned out to be less user-friendly and in many ways less capable than its predecessors in OpenAI's arsenal. It made the same sort of risible errors in answering users' prompts, was no better in math (or even worse), and not at all the advance that OpenAI and its chief executive, Sam Altman, had been talking up.

"The thought was that this growth would be exponential," says Alex Hanna, a technology critic and co-author (with Emily M. Bender of the University of Washington) of the indispensable new book "The AI Con: How to Fight Big Tech's Hype and Create the Future We Want." "Instead, Hanna says, "We're hitting a wall."

The consequences go beyond how so many business leaders and ordinary Americans have been led to expect, even fear, the penetration of AI into our lives. Hundreds of billions of dollars have been invested by venture capitalists and major corporations such as Google, Amazon and Microsoft in OpenAI and its multitude of fellow AI labs, even though none of the AI labs has turned a profit.

Public companies have scurried to announce AI investments or claim AI capabilities for their products in the hope of turbocharging their share prices, much as an earlier generation of businesses promoted themselves as "dot-coms" in the 1990s to look more glittery in investors' eyes.

Nvidia, the maker of a high-powered chip powering AI research, plays almost the same role as a stock market leader that Intel Corp., another chip-maker, played in the 1990s — helping to prop up the bull market in equities.

If the promise of AI turns out to be as much of a mirage as dot-coms did, stock investors may face a painful reckoning.

The cheerless rollout of GPT-5 could bring the day of reckoning closer. "AI companies are really buoying the American economy right now, and it's looking very bubble-shaped," Hanna told me.

The rollout was so disappointing that it shined a spotlight on the degree that the whole AI industry has been dependent on hype.

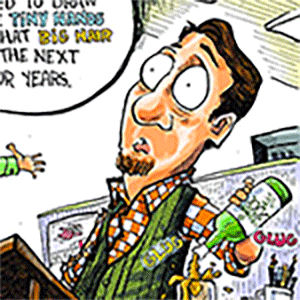

Here's Altman, speaking just before the unveiling of GPT-5, comparing it with its immediate predecessor, GPT-4o: "GPT-4o maybe it was like talking to a college student," he said. "With GPT-5 now it's like talking to an expert — a legitimate PhD-level expert in anything any area you need on demand ... whatever your goals are."

Well, not so much. When one user asked it to produce a map of the U.S. with all the states labeled, GPT-5 extruded a fantasyland, including states such as Tonnessee, Mississipo and West Wigina. Another prompted the model for a list of the first 12 presidents, with names and pictures. It only came up with nine, including presidents Gearge Washington, John Quincy Adama and Thomason Jefferson.

Experienced users of the new version's predecessor models were appalled, not least by OpenAI's decision to shut down access to its older versions and force users to rely on the new one. "GPT5 is horrible," wrote a user on Reddit. "Short replies that are insufficient, more obnoxious ai stylized talking, less 'personality' … and we don't have the option to just use other models." (OpenAI quickly relented, reopening access to the older versions.)

The tech media was also unimpressed. "A bit of a dud," judged the website Futurism and Ars Technica termed the rollout "a big mess." I asked OpenAI to comment on the dismal public reaction to GPT-5, but didn't hear back.

None of this means that the hype machine underpinning most public expectations of AI has taken a breather. Rather, it remains in overdrive.

A projection of AI's development over the coming years published by something called the AI Futures Project under the title "AI 2027" states: "We predict that the impact of superhuman AI over the next decade will be enormous, exceeding that of the Industrial Revolution."

The rest of the document, mapping a course to late 2027 when an AI agent "finally understands its own cognition," is so loopily over the top that I wondered whether it wasn't meant as a parody of excessive AI hype. I asked its creators if that was so, but haven't received a reply.

One problem underscored by GPT-5's underwhelming rollout is that it exploded one of the most cherished principles of the AI world, which is that "scaling up" — endowing the technology with more computing power and more data — would bring the grail of artificial general intelligence, or AGI, ever closer to reality.

That's the principle undergirding the AI industry's vast expenditures on data centers and high-performance chips. The demand for more data and more data-crunching capabilities will require about $3 trillion in capital just by 2028, in the estimation of Morgan Stanley. That would outstrip the capacity of the global credit and derivative securities markets. But if AI won't scale up, most if not all that money will be wasted.

As Bender and Hanna point out in their book, AI promoters have kept investors and followers enthralled by relying on a vague public understanding of the term "intelligence." AI bots seem intelligent, because they've achieved the ability to seem coherent in their use of language. But that's different from cognition.

"So we're imagining a mind behind the words," Hanna says, "and that becomes associated with consciousness or intelligence. But the notion of general intelligence is not really well-defined."

Indeed, as long ago as the 1960s, that phenomenon was noticed by Joseph Weizenbaum, the designer of the pioneering chatbot ELIZA, which replicated the responses of a psychotherapist so convincingly that even test subjects who knew they were conversing with a machine thought it displayed emotions and empathy.

"What I had not realized," Weizenbaum wrote in 1976, "is that extremely short exposures to a relatively simple computer program could induce powerful delusional thinking in quite normal people." Weizenbaum warned that the "reckless anthropomorphization of the computer" — that is, treating it as some sort of thinking companion — produced a "simpleminded view of intelligence."

That tendency has been exploited by today's AI promoters. They label the frequent mistakes and fabrications produced by AI bots as "hallucinations," which suggests that the bots have perceptions that may have gone slightly awry. But the bots "don't have perceptions," Bender and Hanna write, "and suggesting that they do is yet more unhelpful anthropomorphization."

The general public may finally be cottoning on to the failed promise of AI more generally. Predictions that AI will lead to large-scale job losses in creative and STEM fields (science, technology, engineering and math) might inspire feelings that the whole enterprise was a tech-industry scam from the outset.

Predictions that AI would yield a burst of increased worker productivity haven't been fulfilled; in many fields, productivity declines, in part because workers have to be deployed to double-check AI outputs, lest their mistakes or fabrications find their way into mission-critical applications — legal briefs incorporating nonexistent precedents, medical prescriptions with life-threatening ramifications and so on.

Some economists are dashing cold water on predictions of economic gains more generally. MIT economist Daron Acemoglu, for example, forecast last year that AI would produce an increase of only about 0.5% in U.S. productivity and an increase of about 1% in gross domestic product over the next 10 years, mere fractions of the AI camp's projections.

The value of Bender's and Hanna's book, and the lesson of GPT-5, is that they remind us that "artificial intelligence" isn't a scientific term or an engineering term. It's a marketing term. And that's true of all the chatter about AI eventually taking over the world.

"Claims around consciousness and sentience are a tactic to sell you on AI," Bender and Hanna write. So, too, is the talk about the billions, or trillions, to be made in AI. As with any technology, the profits will go to a small cadre, while the rest of us pay the price ... unless we gain a much clearer perception of what AI is, and more importantly, what it isn't.

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments