Sizzling beef prices change how some buy, consume meat

Published in Business News

For a long time, Seattle resident Daniel Lara considered the health and environmental benefits of a plant-based diet. The last spike in beef prices brought him another factor to consider.

At Whole Foods, where Lara shops, the cost of ground beef hit as much as $12.99 per pound earlier this month. For the cost, it is not worth it, he said.

You really have to find ways to save in other areas to try to make up for the expense," Lara said.

Record high beef prices nationwide are a result of myriad factors, including prolonged drought and high feed costs leading to an ongoing decline in cattle numbers. Last year, the U.S. experienced the lowest cattle inventory in more than 70 years, according to the American Farm Bureau, dropping from a surge of 95 million cattle and calves in 2019 to 87.2 million in 2024.

This fall has contributed to skyrocketing meat prices across the nation. The average cost of ground beef, for example, jumped to $6.34 a pound, an 11% increase year over year in June. In the West region, which includes Washington, the average cost for ground beef per pound was around $6.29 in June, up more than 10% year over year.

In late July, prices in Seattle stores trended higher. The cost of ground beef at a Seattle QFC store ranged from around $6.99 to $11.99 per pound. At Safeway in the University District, prices started at $8.49 per pound.

While rising prices are squeezing Seattle-area shoppers and meat businesses, they are creating opportunities for some local ranchers to gain new customers while trying to maintain thin profits.

Jim Anderson, owner of Triple A Cattle Co., a Stanwood, Washington-based ranch, said ever since beef prices jumped in grocery stores, business has been popping.

“Our phone rings off the hook for people wanting to buy beef because of the price of beef in the store,” Anderson said.

“Extremely resilient”

The cattle industry is a major pillar of Washington’s economy — accounting for about $2.17 billion per year. But the changing landscape is forcing those who raise, sell and buy the meat to find ways to adapt.

Despite slight decreases, herds in Washington have remained fairly steady, said Jackie Madill, executive director at the Washington State Beef Commission.

While the cost of doing business for ranchers has increased, Madill said, Washington’s beef industry is “extremely resilient.” The number of cattle is decreasing slightly, but the actual pounds of beef being produced is still stable.

Similar to national trends, the decline in Washington cattle is an outcome of drought and high feed costs, among others. Drought conditions cover nearly 94% of the state, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, leading to less available grass for cattle to graze on. To supplement food, ranchers buy hay and other feed, boosting the cost of production.

To keep those costs down, some Washington ranchers have downsized their herds, leading to a raise in value for the protein. And because people are still willing to buy beef, ranchers, who work on extremely narrow profit margins, aren’t lowering costs.

“Cattle are at their highest value right now,” Madill said.

As cattle numbers decline in the U.S., imports of beef from foreign countries have increased to fill in demand, Madill said, with data from the Department of Agriculture estimating that import volumes of beef will peak this year at 4.4 billion pounds. In 2024, foreign beef imports increased by 10%, according to a statement from the Meat Import Council of America.

Ranchers find themselves at the center of an increasingly expensive industry.

“When it comes to supply and demand economics, the cost of doing business within the cattle industry and beef industry has gone up,” Madill said. “So is that pressure on those producers, and we see that trickling into price pressure on consumers.”

“It’s an absolute game changer”

Anderson, owner of Triple A Cattle, is one of the producers who is feeling the pressure.

A lifelong rancher, Anderson is one of the over 9,000 family ranchers in Washington. He opened Triple A in Snohomish County, Washington, in 2011, and now has about 170 heads of cattle in his herd.

Anderson doesn’t sell to large wholesalers, instead he markets straight to consumers. His biggest expenses, he said, have been the cost of production as well as fuel, feed and the cattle itself.

Because his business is in Western Washington, he isn’t feeling the drought impacts as heavily as Greg Newhall, who owns Windy N Ranch in Kittitas County, Washington.

Newhall said drought has forced him to supplement grass grazing with feed.

For the last three years, he said, the water the ranch has paid for has been cut off early due to drought conditions. This year, the farm will get less than half the irrigation water it pays for.

He owns about 520 cattle, 120 being mothers. Newhall sells directly to consumers because, he said, he enjoys working closely with people and doesn’t have enough cattle or money to be in the commercial market.

Like Anderson, Newhall said demand hasn’t slowed, but because the margins of cattle raising are already extremely thin, not being able to grass feed the cattle has further shrunk profits.

“It’s an absolute game changer and crushes any margins that you might think that you have,” Newhall said.

Unlike some perceptions, Newhall said, most cattle ranchers are unable to solely live off their livestock. The average size of a cattle herd in the U.S. is about 47 head, according to the Department of Agriculture, and with cattle on an 8-to 12-year production cycle, most ranchers also have jobs in town.

As the U.S. grows more dependent on imported beef, Newhall said he worries about how tariffs placed by President Donald Trump are going to impact the industry internally and externally, as they trigger retaliatory levies on U.S. exports. Beef was Washington’s eighth-highest export last year.

“It’s a very unstable market right now,” Newhall said. “It’s a little scary.”

Both Anderson and Newhall are hopeful that pricier beef will benefit all ranchers by making cattle more valuable. And with sales not slowing down, both ranchers feel confident that people are still willing to shell out for the protein.

Looking for 'cheaper food'

Not all sectors of the industry are feeling as hopeful about the market though. Some Seattle meat shops tell a different story.

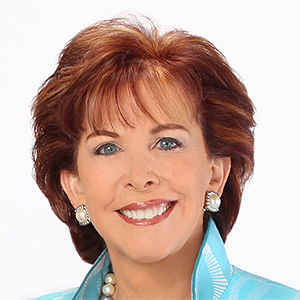

Kim Nygard, owner of Double DD Meats in Mountlake Terrace, said prices have been rising with inflation since the COVID-19 pandemic, but in the last couple of months, costs have soared. The butcher shop sources from local and international markets, bringing in meat all the way from New Zealand.

“Normally I don't have to check the prices every day when our meat comes in,” Nygard said. “Now, I do.”

To deal with the costs, Nygard said she’s raised prices by about 10% to 15% in the last couple of months. One pound of lean ground beef is currently $7.98, she said. While this is more costly than most grocery store prices, Nygard said it’s a higher quality cut, with the beef trimmed off steaks and ground in house.

Despite upping her prices, Nygard said demand has remained steady.

“It’s been busy,” Nygard said. “70s is the perfect barbecue weather. It makes people hungry.”

But some make compromises to keep the grill season going.

Bernie Laird, 21, has stopped buying fancier cuts such as steaks and switched to ground beef to save costs. Laird usually shops at Town & Country Market, formerly called Central Market, where a pound of ground beef ranges from $6.99 to $14.49.

Laird studies computer science at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis and lives in the Twin Cities during the school year. When he came back for the summer, he noticed the increase in grocery prices, calling them “a lot” in Seattle. To save on grocery costs in the summer, he’s made a switch across the board to cheaper food.

“My budget isn’t increasing as fast as grocery prices are,” Laird said.

Some aren’t willing to shell out for the meat anymore, according to John Carlo Pineda, an assistant manager at B & E Meats & Seafood, a Washington butcher shop with a location in the Queen Anne neighborhood of Seattle.

The shop sources almost all of its meat locally, stretching only as far as Montana.

Starting this month, Pineda said prices became extremely high, hitting sales. Pineda said he’s seen customers leave the shop or move onto cheaper proteins due to prices.

The shop is trying to find solutions while still offering the best quality cuts, but Pineda said it has begun to hurt income.

“Customers are getting sticker shock,” he said.

©2025 The Seattle Times. Visit seattletimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments