Minnesota farmers seek state aid as foreclosure crisis looms

Published in Business News

MORGAN, Minnesota — Beneath the surface of Farmfest’s tractor sales and herbicide chats this week is a brewing financial crisis for Minnesota’s farmers.

Hundreds have asked the state to intervene with their bankers, a midsummer level not seen since 2016, according to the University of Minnesota Extension.

“Every year anymore, there’s 20 percent who really struggle,” said Garen Paulson, an extension educator in Lamberton who specializes in business management. “That doesn’t sound like a lot, but think of your neighbors. That’s a pretty good size measure.”

In June, 197 farmers filed notice for help from the Extension’s Farmer-Lender Mediation program. July was even worse with 306 notices, a four-fold increase over the same month last year.

The upending of global trade has ignited farmer anxiety and resurfaced haunting memories of the 1980s farm crisis that devastated rural Minnesota and other swaths of the heartland.

Gene Stengel, who has farmed in Yellow Medicine County since the early 1970s, said the markets’ nosedive has made him consider the once-unthinkable: potentially selling off land or assets.

“You can’t sustain the losses,” he said. “It’s going to force sales.”

Stengel said his banker told him there was little wiggle room on his loans, including refinancing. He has until January to decide.

“It’s stressful, stressful,” Stengel said. “And it’s all related to the markets.”

Inflation and falling land prices drove the economic woes of the ’80s; the current downturn in agriculture, which is a $106 billion industry in Minnesota, is linked to low commodity prices — particularly for corn and soybeans.

This August, soybeans, which are Minnesota’s largest export at more than $4 billion, trade for less than $10 a bushel. In spring 2024, farmers could fetch more than $12 a bushel.

Prices were soft before President Donald Trump returned to office in January, with American farmers increasingly ceding markets to Brazil and Argentina, analysts say. But the administration’s retaliatory tariffs have stunted any recovery.

“We’re seeing this administration handling trade differently,” Zippy Duvall, president of the American Farm Bureau Federation. “Are we confident that’s going to work? I don’t know if anybody’s confident it’s going to work.”

The state’s Farmer-Lender Mediation program, which was born out of the 1980s turbulence, allows a “cooling-off period” that puts farmers on a payment plan to at least temporarily avoid a foreclosure, said Extension Dean Beverly Durgan.

“No loans can be called, and all the creditors come to the table with the farmers,” Durgan said.

Peter Ripka, who raised dairy cows for 35 years outside Ogilvie in north central Minnesota, knows the state’s mediation well. In 2018, with mounting health costs from injuries on the job, he resolved to sell his herd.

But the bank called the loan before he could, and the Extension’s mediation was a critical intervention.

With access to the Twin Ports in Duluth and the Mississippi River, as well as rail lines to the West Coast, Minnesota is a strong source for agricultural exports, producing more soybeans and corn than all but a few states.

For the second year in a row, soybean farmers fear they might lose money on every acre they plant. Corn growers expect a bumper crop, yet they’ll see measly prices, hovering just above $4 a bushel.

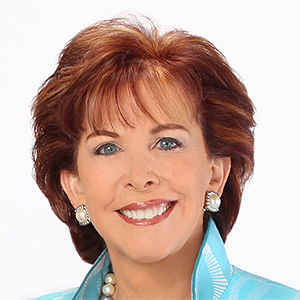

“I’ve heard people are scared,” said Sen. Amy Klobuchar, the Minnesota Democrat who is the ranking member on Senate Agriculture Committee, speaking on Tuesday at Farmfest. “When these tariffs hit, they drive away markets, and [those export markets] don’t come back.”

Other than a short spike right after the pandemic, crop prices have been depressed since the 2018-2020 trade wars from Trump’s first administration and largely continued under President Joe Biden. Further tariff increases this year, with the possibility of more, have heightened uncertainty in the commodities markets.

The result has been a slow march toward a reshaped global trade system for Midwestern corn and soybean farmers. After enjoying decades of global market expansion, many are now staring at unmanageable amounts of debt.

Costs have increased sharply in the past few years.

Seed, fertilizer and farmland rental rates are higher, said Sam Ziegler, director of GreenSeam, a southern Minnesota agriculture initiative. So are insurance costs due to flooding, hail and windstorms of the past few years. Aging farmers pay more for health care costs. And on increasingly digitized farms, cybersecurity is increasingly expensive.

“If you lose money today, you’re going to lose a lot more, a lot faster,” said Ziegler, who also farms outside Good Thunder.

Farmers in turn are tightening their belts. Two years ago, 50% of agricultural businesses in Minnesota said they plan to hire more employees, Ziegler said. This year, only 38% said they were expanding.

Farmers also are spending less on big ticket purchases, which has affected dealerships and tractor manufacturers.

Paul Link, director of sales at Vaderstad, watched over the Swedish company’s Farmfest booth this week. He said many farms are trying to get by with older equipment.

“It’s definitely affected us,” with lower sales over the past 12 to 16 months, he said. “I think the unfortunate part is, we’re not quite out of the woods yet.”

There’s little indication when relief will come.

U.S. Rep. Brad Finstad, who farms near New Ulm, said a disaster relief bill passed by Congress late last year provided a crucial “injection of money” to help farmers get through to the current growing season.

While many farmers mourn the loss of market share in China since 2018, the Republican and supporter of Trump’s trade policies argued that the U.S. had put too many of its “eggs in one basket,” allowing Beijing to dictate prices.

“We need new opportunities to expand who wants to buy our products,” Finstad said.

The politics of government farm policy is hard for some farmers to concentrate on when they are struggling to keep their operations afloat.

David Syring, who grows corn and soybeans on 1,500 acres near Granite Falls with his father, lost about 20% of his crops when heavy rains fell on southwestern Minnesota in June.

He doesn’t expect to make money this year.

But Syring said he and other farmers will have to keep living on hope and faith that next year will be better.

“There’s a lot more harder days than there’s easy ones,” Syring said. “But I can’t imagine a different life.”

(Allison Kite contributed to this story.)

©2025 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit at startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments